Whether he's trashing Anita Hill or habeas corpus, Arlen Specter can always be counted on to do . . . well, what he thinks is best for him

habeas corpus, Arlen Specter can always be counted on to do . . . well, what he thinks is best for him'>habeas corpus, Arlen Specter can always be counted on to do . . . well, what he thinks is best for him'>habeas corpus, Arlen Specter can always be counted on to do . . . well, what he thinks is best for him'>habeas corpus, Arlen Specter can always be counted on to do . . . well, what he thinks is best for him'>>habeas corpus, Arlen Specter can always be counted on to do . . . well, what he thinks is best for him'>

"If Specter has accommodated his views to his party's, his leisure habits have not changed: he still plays squash seven days a week, a routine that he has maintained since the nineteen-seventies."

"If Specter has accommodated his views to his party's, his leisure habits have not changed: he still plays squash seven days a week, a routine that he has maintained since the nineteen-seventies."--Jeffrey Toobin, in "Killing Habeas Corpus," in the current (Dec. 4) New Yorker

Now Jeffrey Toobin is a fine writer on legal matters, and I enthusiastically commend this piece, which works a pretty decent profile of Arlen Specter into an excellent chronicle of the passing of the appalling Military Commissions Act of 2006, one of the low points of even this mind-numbingly dreadful session of Congress. But I keep coming back to this sentence.

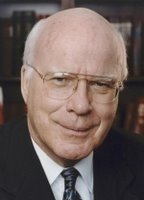

Every writer, I imagine, gets stuck. One of the most familiar ways is the need for some sort of transition to get you from point A to point B when there really isn't any logical one. And maybe that's all that happened to Toobin (pictured at left) here. Having accomplished his tidy survey of the flips and flops of Specter's political survival, he wants to get into the subject of the senator's pretty remarkable literal survival, highlighted by his grimly determined battles against a brain tumor in 1993 (when he "was told that he had three to six weeks to live") and his late-2004 diagnosis of Hodgkin's disease ("during the first several months of his tenure as chairman of the Judiciary Committee [in 2005] he received chemotherapy," and he "never stopped playing squash").

Every writer, I imagine, gets stuck. One of the most familiar ways is the need for some sort of transition to get you from point A to point B when there really isn't any logical one. And maybe that's all that happened to Toobin (pictured at left) here. Having accomplished his tidy survey of the flips and flops of Specter's political survival, he wants to get into the subject of the senator's pretty remarkable literal survival, highlighted by his grimly determined battles against a brain tumor in 1993 (when he "was told that he had three to six weeks to live") and his late-2004 diagnosis of Hodgkin's disease ("during the first several months of his tenure as chairman of the Judiciary Committee [in 2005] he received chemotherapy," and he "never stopped playing squash").And yet, there is that bizarre transition. There is no question in Toobin's mind, and certainly not in his account, that Specter has indeed "accommodated his views to his party's," meaning that he has submerged his famous "moderate" political views to those prevailing in his party. It was clear pretty much overnight, for example, when the Republicans retook control of the Senate in the 2004 election:

At a press conference on the day after he was reëlected in 2004, Specter repeated a view he had expressed many times, saying that he regarded the protection of abortion rights established by Roe v. Wade as "inviolate," and suggesting that "nobody can be confirmed today" who didn't share that opinion. Almost immediately, conservative groups in the Republican Party demanded that Specter be denied the chairmanship. Protesters chanted outside his office and inundated the Senate switchboard with telephone calls.

After a series of tense meetings with his Republican colleagues, Specter was allowed to take over as chairman of the committee, but he had to make certain promises, especially about Bush's nominations to the Supreme Court. "I have voted for all of President Bush's judicial nominees in committee and on the floor," Specter said in a carefully worded statement at the time. "And I have no reason to believe that I'll be unable to support any individual President Bush finds worthy of nomination." In the subsequent two years, Specter was as good as his word, shepherding the nominations of John G. Roberts, Jr., and Samuel A. Alito, Jr., to confirmation to the Supreme Court. Nearly two decades earlier, Specter had provided a key vote against Ronald Reagan's nomination of Robert H. Bork to the Court, but as chairman of the Judiciary Committee he became an advocate for two new Justices whose views resembled Bork's.

And, as Toobin's chronicle shows, Specter's willing accommodation to the Right became clear again in the battle over the rights of "enemy combatant" detainees, where he wound up voting for a bill that--in fairly clear violation of the Constitution--legislates the suspension of perhaps this country's most fundamental legal right, that of habeas corpus.

I'm sure that Toobin knows there's nothing logical about this transition. What on earth could Specter's squash-playing have to do with his political twisting and turning?

But maybe Specter, the happily outgoing chairman of the Judiciary Committee (come on--Arlen Specter for Pat Leahy [right]? talk about a one-sided trade) just lends himself to curious transitions. He is one of the more curious denizens of the Senate in my alarmingly long time observing it. Not one of the best, or even one of the better senators. At the same time, certainly not one of the worst. (There's always heavy competition for that distinction.) There's just something, well, curious about him and his career that keeps drawing you back. Well, keeps drawing me back anyway.

But maybe Specter, the happily outgoing chairman of the Judiciary Committee (come on--Arlen Specter for Pat Leahy [right]? talk about a one-sided trade) just lends himself to curious transitions. He is one of the more curious denizens of the Senate in my alarmingly long time observing it. Not one of the best, or even one of the better senators. At the same time, certainly not one of the worst. (There's always heavy competition for that distinction.) There's just something, well, curious about him and his career that keeps drawing you back. Well, keeps drawing me back anyway.Maybe the thing is that Specter himself probably thinks he numbers among the handful of greatest senators in the history of our republic. He would probably be happy to tell you so, without your even asking.

What can make Specter's Senate career so tricky is that Pennsylvania has an authentic tradition of prominent moderate Republicans, people like onetime Gov. William Scranton and Sens. Hugh Scott and John Heinz. Specter made believe he came in that tradition. And maybe, in less poisoned political times, he was--that is, before the Republican Party sold its soul to the devil.

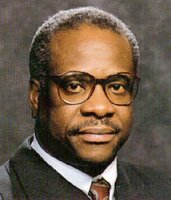

The juxtaposition of Specter with Heinz [right] is curious. Specter entered the Senate in 1981, four years after Heinz, and they served together for 10 years. The plane crash that killed Heinz leaves us no way of knowing how he would have responded to the changing political times. He died on April 4, 1991. As an example, the Supreme Court nomination of Clarence Thomas--which we're about to talk about--was announced by the first President Bush three months later, on July 8.

The juxtaposition of Specter with Heinz [right] is curious. Specter entered the Senate in 1981, four years after Heinz, and they served together for 10 years. The plane crash that killed Heinz leaves us no way of knowing how he would have responded to the changing political times. He died on April 4, 1991. As an example, the Supreme Court nomination of Clarence Thomas--which we're about to talk about--was announced by the first President Bush three months later, on July 8.For most of us, it's easy to date Specter's ascension to the upper ranks of the Public Enemy list: Clarence Thomas's 1991 Supreme Court confirmation battle. The televised Senate Judiciary Committee hearings in which Anita Hill testified to what she claimed was Thomas's repellent behavior when he was her boss at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission offered a rare glimpse into two wildly different philosophies of governing, indeed of life:

The committee Democrats, headed by then-chairman Joseph Biden, quaintly assumed that it was their job to get the facts. The Republicans, however, clearly didn't give a damn about the facts; all they wanted was to get their way--in this case, to ram the Thomas nomination through, no matter what it took. And what it took, from Senator Specter, was a vile trashing of Hill that had nothing to do with the facts. Drawing on his experience as a prosecutor, he did a dance of crude character assassination.

Of course I can't say for sure what Specter did or didn't know. I can only say that he's not a moron, and it seemed to me pretty clear at the time of the Thomas-Hill hearings that only a moron could possibly not know that Hill was telling the truth and Thomas was lying. It should have been a matter of personal embarrassment that there were morons among the Republicans on the Judiciary Committee at the time, but as far as Anita Hill was concerned, it really didn't matter. The committee Republicans' marching orders were to get Clarence Thomas confirmed, and that's what they were by God going to do--facts, schmacts.

Of course I can't say for sure what Specter did or didn't know. I can only say that he's not a moron, and it seemed to me pretty clear at the time of the Thomas-Hill hearings that only a moron could possibly not know that Hill was telling the truth and Thomas was lying. It should have been a matter of personal embarrassment that there were morons among the Republicans on the Judiciary Committee at the time, but as far as Anita Hill was concerned, it really didn't matter. The committee Republicans' marching orders were to get Clarence Thomas confirmed, and that's what they were by God going to do--facts, schmacts.Astonishingly, though, Specter seems to think that his disgraceful conduct in those hearings is grounds for pride:

In his autobiography, "Passion for Truth" (2000), he writes with pride about his work as a young investigator for the Warren Commission; as a crusading Philadelphia district attorney; and as an aggressive cross-examiner of Anita Hill in Clarence Thomas's Supreme Court confirmation hearings. He has, he wrote, a "fetish for facts," and faith in proceedings like habeas corpus to protect individual rights

I don't know what it all goes to show. I guess maybe that there is a breed of politician as dangerous as, if not more dangerous than, the easy-to-read extremist ideologues like former Sens. Jesse Helms and Rick Santorum or former House Speaker Newt Gingrich. These are the people who claim to be pragmatists guided by unshakable (indeed often biblical) principle, and yet who on closer inspection seem to have no principle higher than their own self-adoration.

Thinking about these people usually depresses me, and my response to the Toobin New Yorker piece has been no exception. The one surprise is that in this round of morbid speculation, I've found myself shading into thinking about the nearest thing Arlen Specter has to a senatorial twin, another legend in his own mind, Holy Joe Lieberman. You get that same smarmy, smug self-certainty, with an added layer of unpleasantness that may be generational, a product of the fact that Holy Joe is a dozen years younger: the heavy tinge of corruption in his career, the cash-and-carry history of corporate whoring that makes his quasi-rabbinical pretensions even more obnoxious.

(Somebody is bound to point out the disturbing coincidence, if it is a coincidence, that Specter and Lieberman are both Jewish. I'm just pointing it out before someone hurls the deadly charge of anti-Semitism. In fact, I and most of the Jews I know rate both of them high on our enemies' list. And I would point out that Holy Joe has gone even farther than our Arlen toward making himself the anti-Semites' favorite Jew.)

Jeez, now I'm really depressed.

2 Comments:

If people accuse you of being an anti-Semite, I know of the perfect response. What explains the left's love affair with Feingold? Is it because Lieberman and Specter have sold their soul to the political devil? Is it because Feingold is a champion of the small guy(being one himself)? The truth of the matter is, Specter and Lieberman suck, no matter what their religion. The press treats them like moderates when they are nothing of the kind. That is why I believe they are more despised than Frist or Hastert or Gingrich. With guys like Frist, you know where they stand at all times and they make no apologizes for it. Specter and Holy Joe try to play both sides, and the media has to stop sucking up to these two.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

Post a Comment

<< Home