Quote of the day: (2) Elsewhere in the news—Still more horror in Iraq, while the guys Paul Krugman refers to as "the crazies" are talking, well, crazy

>

"I get excited when fantasy football season's coming. This guy gets excited when war season's coming."

—Paul Rieckhoff, founder and executive director of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, talking to Rachel Maddow this morning about Weekly Standard editor and renowned neocon nutjob Bill Kristol, who has been gleefully calling for bombing Iran

No, no, Paul Rieckhoff isn't one of "the crazies." He's one of the good guys—a leading voice for Afghanistan and Iraq vets and a famously serious thinker about war issues. He and Rachel agreed that it's time to stop talking about whether we should get out of Iraq and instead talk about how. Paul suggested that the discussion is already under way, qualifying his suggestion to refer to discussion that's taking place outside the Beltway.

No, no, Paul Rieckhoff isn't one of "the crazies." He's one of the good guys—a leading voice for Afghanistan and Iraq vets and a famously serious thinker about war issues. He and Rachel agreed that it's time to stop talking about whether we should get out of Iraq and instead talk about how. Paul suggested that the discussion is already under way, qualifying his suggestion to refer to discussion that's taking place outside the Beltway.At this point I have to make a confession. I don't really take in a lot of detail about the war—in either Afghanistan or Iraq. Every day I figure I get the gist, with enough specifics from the radio or from newspaper photos. I just can't immerse myself in that nauseatingly gory detail every day.

Today, however, something made me look at a story on the front page of the New York Times, under the headline "Sects' Strife Takes a Toll on Baghdad's Daily Bread," by Sabrina Tavernise, with reporting contributed by Hosham Hussein.

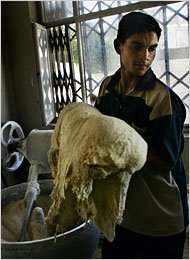

Probably it was the reference to "daily bread" that caught my eye—I'm always attracted to nuts-and-bolts stuff, stuff that relates to the daily business of living. And indeed the focus of the story is an apparently deliberate attempt by the militias to cut off the daily bread supply by murdering or otherwise shutting down (predominantly Shiite) bakers.

Probably it was the reference to "daily bread" that caught my eye—I'm always attracted to nuts-and-bolts stuff, stuff that relates to the daily business of living. And indeed the focus of the story is an apparently deliberate attempt by the militias to cut off the daily bread supply by murdering or otherwise shutting down (predominantly Shiite) bakers.Pictured here is the principal quoted source for the story, a 23-year-old Shiite baker named Edrice al-Aaraji (who's still alive—at least as of this writing, at least as far as I know), doing what he should be doing, which is to say making bread.

If you read only one story about the war this week, I recommend this one. But let me warn you that if you've eaten recently, you'll have difficulty keeping the food down, and if you read the piece in a public place—the subway, for example—you have to be prepared to find yourself bawling publicly.

"A year ago, when some of the first bakers were killed, Iraqis in the capital dismissed the deaths as a bizarre aberration," Tavernise reports. "Civil war is not possible here, they said. Sunnis and Shiites have intermarried for generations, they said, and Iraqis will not fight Iraqis on the basis of sect.

"For months Iraqis held on to the belief that sectarian attacks were carried out by outsiders, but the bombing of a Shiite shrine in February, after which Shiite militias went on a rampage, dragging Sunnis out of mosques and homes and killing them, shattered that. The unrelenting violence has hardened Iraqis against one another, and people talk in resigned tones about civil war."

I just reread the following story, and it had me in tears again:

One morning in late June, in a bakery in a heavily Shiite district, men with guns in plain clothes blindfolded and handcuffed 10 workers and marched them into four cars, according to the Iraqi authorities and the cousin of one of the workers who was taken.

The workers, Sunni and Shiite, were asked questions in an ordinary house about where they were from, the names of their city council members and the imams of their mosques. Several hours later, all but two—Sunni Arabs from the same tribe—were released.

The two men, brothers in their early 20’s, were friends with their Shiite colleagues for years. They all lived together in the mixed neighborhood of Hurriya. The Shiites pulled every string they could to free them, calling powerful political parties and police and army contacts.

A week later, the men’s bodies were found. They were killed, shot in the head, according to an autopsy, on the same day that a bomb killed 62 people in Sadr City, a Shiite stronghold. Some Shiite workers attended the funeral.

The man who provided the account said his cousin, one of the abductees, still weeps when their names come up. He, like many interviewed, spoke anonymously for fear of reprisals.

Tavernise goes on to report widespread bitterness among Iraqis that the American military does nothing.

“Their main task, their whole reason for being here, is to prevent exactly this, but they do nothing,” said an Iraqi mother who lives near Sadr City and strongly supported the Americans as recently as last year. “They just let it go, my God, so easily.”

Tavernise adds these stories from the young baker Edrice al-Aaraji:

This summer, Mr. Aaraji’s cousin, a tire repairman, was shot dead by Sunni militants. They entered the shop where he was working and asked to look at his identification card, Mr. Aaraji said. His name, Ali, was Shiite.

This summer, Mr. Aaraji’s cousin, a tire repairman, was shot dead by Sunni militants. They entered the shop where he was working and asked to look at his identification card, Mr. Aaraji said. His name, Ali, was Shiite.“Kitlo,” Mr. Aaraji said, meaning “they killed him.”

“It has become normal,” he said, bowing his head slightly and dragging on his cigarette.

He took the recent shooting death of a Shiite friend in stride, because the man had refused to change the ring on his cellphone, a short musical quip insulting Wahhabis, hard-line Sunni Arabs. “We knew it would provoke them,” he said. “We told him to change it.

“They put four bullets in his head.”

In a neighboring story, "More Iraqis Fleeing Strife and Segregating by Sect" (a trend well-documented in Tavernise's story), Damien Cave quotes U.S. military spokesman Maj. Gen. William B. Caldwell IV (right) "acknowledg[ing] that 50,000 Iraqi forces and 7,200 American troops were struggling to protect Baghdad. 'We have not witnessed the reduction in violence one would have hoped for in a perfect world,' General Caldwell said. He predicted that it would 'take months not weeks' to make Baghdad safe."

In a neighboring story, "More Iraqis Fleeing Strife and Segregating by Sect" (a trend well-documented in Tavernise's story), Damien Cave quotes U.S. military spokesman Maj. Gen. William B. Caldwell IV (right) "acknowledg[ing] that 50,000 Iraqi forces and 7,200 American troops were struggling to protect Baghdad. 'We have not witnessed the reduction in violence one would have hoped for in a perfect world,' General Caldwell said. He predicted that it would 'take months not weeks' to make Baghdad safe."If you're still with me, you should be in the perfect frame of mind now to read Paul Krugman's column today, "The Price of Fantasy," which begins:

Today we call them neoconservatives, but when the first George Bush was president, those who believed that America could remake the world to its liking with a series of splendid little wars—people like Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld—were known within the administration as “the crazies.” Grown-ups in both parties rejected their vision as a dangerous fantasy.*

"The second President Bush," Krugman writes, "obviously confuses swagger with strength, and prefers tough talkers like the crazies to people who actually think things through. He got the chance to implement the crazies’ vision after 9/11, which created a climate in which few people in Congress or the news media dared to ask hard questions. And the result is the bloody mess we’re now in."

Iraq was targeted, Krugman has been insisting for years now, "not because it posed a real threat, but because it looked like a soft target"—thereby, ironically, emboldening countries like North Korea and Iran, which actually do pose a threat to us. Meanwhile:

Few if any of the crazies have the moral courage to admit that they were wrong. Vice President Cheney continues to insist that his two most famous pronouncements about Iraq—his declaration before the invasion that we would be “greeted as liberators” and his assertion a year ago that the insurgency was in its “last throes”—were “basically accurate.”

Which brings us back to renowned neocon nutjob Bill Kristol (bloviating at right). Krugman writes:

Which brings us back to renowned neocon nutjob Bill Kristol (bloviating at right). Krugman writes:The crazies respond by retreating even further into their fantasies of omnipotence. The only problem, they assert, is a lack of will.

Thus William Kristol, the editor of The Weekly Standard, has called for a military strike—an airstrike, since we don’t have any spare ground troops—against Iran.

“Yes, there would be repercussions,” he wrote in his magazine, “and they would be healthy ones.” What would these healthy repercussions be? On Fox News he argued that “the right use of targeted military force” could cause the Iranian people “to reconsider whether they really want to have this regime in power.” Oh, boy.

You have to wonder whether, in the neocon think tanks where the determination to Iraq was determined, and fantasies were fantasized about Iraqis greeting Americans as liberators and becoming Israel's best friend . . . as I say, you really have to wonder whether the delicate neoncon geniuses ever thought about the possibility of Baghdad bread bakers being systematically wiped out.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

*As usual, in case the link doesn't work, the full text of the Krugman column is posted in a comment. If any of the other links don't work, please let me know.

2 Comments:

New York Times

July 21, 2006

Op-Ed Columnist

The Price of Fantasy

By PAUL KRUGMAN

Today we call them neoconservatives, but when the first George Bush was president, those who believed that America could remake the world to its liking with a series of splendid little wars — people like Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld — were known within the administration as “the crazies.” Grown-ups in both parties rejected their vision as a dangerous fantasy.

But in 2000 the Supreme Court delivered the White House to a man who, although he may be 60, doesn’t act like a grown-up. The second President Bush obviously confuses swagger with strength, and prefers tough talkers like the crazies to people who actually think things through. He got the chance to implement the crazies’ vision after 9/11, which created a climate in which few people in Congress or the news media dared to ask hard questions. And the result is the bloody mess we’re now in.

This isn’t a case of 20-20 hindsight. It was clear from the beginning that the United States didn’t have remotely enough troops to carry out the crazies’ agenda — and Mr. Bush never asked for a bigger army.

As I wrote back in January 2003, this meant that the “Bush doctrine” of preventive war was, in practice, a plan to “talk trash and carry a small stick.” It was obvious even then that the administration was preparing to invade Iraq not because it posed a real threat, but because it looked like a soft target.

The message to North Korea, which really did have an active nuclear program, was clear: “The Bush administration,” I wrote, putting myself in Kim Jong Il’s shoes, “says you’re evil. It won’t offer you aid, even if you cancel your nuclear program, because that would be rewarding evil. It won’t even promise not to attack you, because it believes it has a mission to destroy evil regimes, whether or not they actually pose any threat to the U.S. But for all its belligerence, the Bush administration seems willing to confront only regimes that are militarily weak.” So “the best self-preservation strategy ... is to be dangerous.”

With a few modifications, the same logic applies to Iran. And it’s easier than ever for Iran to be dangerous, now that U.S. forces are bogged down in Iraq.

Would the current crisis on the Israel-Lebanon border have happened even if the Bush administration had actually concentrated on fighting terrorism, rather than using 9/11 as an excuse to pursue the crazies’ agenda? Nobody knows. But it’s clear that the United States would have more options, more ability to influence the situation, if Mr. Bush hadn’t squandered both the nation’s credibility and its military might on his war of choice.

So what happens next?

Few if any of the crazies have the moral courage to admit that they were wrong. Vice President Cheney continues to insist that his two most famous pronouncements about Iraq—his declaration before the invasion that we would be “greeted as liberators” and his assertion a year ago that the insurgency was in its “last throes”—were “basically accurate.”

But if the premise of the Bush doctrine was right, why are things going so badly?

The crazies respond by retreating even further into their fantasies of omnipotence. The only problem, they assert, is a lack of will.

Thus William Kristol, the editor of The Weekly Standard, has called for a military strike—an airstrike, since we don’t have any spare ground troops—against Iran.

“Yes, there would be repercussions,” he wrote in his magazine, “and they would be healthy ones.” What would these healthy repercussions be? On Fox News he argued that “the right use of targeted military force” could cause the Iranian people “to reconsider whether they really want to have this regime in power.” Oh, boy.

Mr. Kristol is, of course, a pundit rather than a policymaker. But there’s every reason to suspect that what Mr. Kristol says in public is what Mr. Cheney says in private.

And what about The Decider himself?

For years the self-proclaimed “war president” basked in the adulation of the crazies. Now they’re accusing him of being a wimp. “We have been too weak,” writes Mr. Kristol, “and have allowed ourselves to be perceived as weak.”

Does Mr. Bush have the maturity to stand up to this kind of pressure? I report, you decide.

no he doesn't, he is a sick amoral person and should be put down like a dog

a airstrike against the crazies is what is needed

Post a Comment

<< Home