Here's a DWT Christmas post, complete with a professorial case that it's a holiday "for us all"--or try celebrating the way Handel and Berlioz did

>

"The whole truth about Christmas . . . reveals why all can enjoy it. It is the perfect example of America's mainstream process, a national rite that dissolves the boundaries between sacred and secular, pagan and civilized, insiders and outsiders."

"The whole truth about Christmas . . . reveals why all can enjoy it. It is the perfect example of America's mainstream process, a national rite that dissolves the boundaries between sacred and secular, pagan and civilized, insiders and outsiders."--Harvard sociology professor and current New York Times guest columnist Orlando Patterson, in his column today, "A Holiday for Us All"

Anyone who's read DWT a bit may have picked up the hint that among those of us who hang out here, Howie and I at least aren't exactly religiously fervid.

I am prepared to acknowledge, at least, that over the millennia there have been a large number of sincerely religious people whose religiosity led them to do good deeds and live good lives, lives that improved those of at last some portion of their fellow humans.

But then you have to set against that the routine destruction and even monumental evil perpetrated through history in the name of religion. Not to mention its apparently irresistible invitation to authoritarian control among the leaders (sometimes just for the sake of power itself, sometimes for profit, often for both), and surrender of mind and will, and with them moral responsibility, among the followers. Not a pretty picture.

But then you have to set against that the routine destruction and even monumental evil perpetrated through history in the name of religion. Not to mention its apparently irresistible invitation to authoritarian control among the leaders (sometimes just for the sake of power itself, sometimes for profit, often for both), and surrender of mind and will, and with them moral responsibility, among the followers. Not a pretty picture.But it's Christmas! How could anyone except Scrooge himself be a Scrooge on Christmas?

Don't try saying that to that puling pussyboy Bill O'Reilly or his fellow psychopaths who have dreamed up the bizarre psychotic fantasy that somebody has stolen Christmas, indeed that Christianity itself is somehow under siege here in the U.S. of A. Really now, what the heck is the point of having loony bins if it's not keep brain-damaged people like that from posing a threat to themselves and especially to the rest of us?

Anyhow, the point I was getting at is that DWT is not the optimal place to come for a heapin' helpin' o' Christmas cheer. About the best I can come up with--and it's not nearly as entertaining as the recent Studio 60 vivisection of the holiday--is this erudite pro-Christmas column by Orlando Patterson. (Although I think he thinks he's said the final word on the subject, I will actually have a more final word after he's had his holiday say.)

December 23, 2006

Guest Columnist

A Holiday for Us All

By ORLANDO PATTERSONChristmas seems to bring out the worst in America's culture warriors. The Christian right continues its crusade against those waging "war against Christmas." Multiculturalists have nearly banished "Merry Christmas" and "Silent Night" from the public domain and are now going after outdoor Christmas trees. Atheist activists like Sam Harris are goaded into defending the outing of their Christmas trees with the argument that it's all secular anyway.

Harris is only partly right. The whole truth about Christmas is far more interesting and reveals why all can enjoy it. It is the perfect example of America's mainstream process, a national rite that dissolves the boundaries between sacred and secular, pagan and civilized, insiders and outsiders.

From the very beginning Christians have always had a tenuous hold on the holiday. The tradition of celebrating Jesus' birth on the 25th of December was invented in the fourth century in a proselytical move by the Church Fathers that was almost too clever. The pre-Christian winter solstice celebrations of the rebirth of the sun, especially the Roman Saturnalia and Iranian Mithraic festivals, were recast as the Christian doctrine of the re-birth of the Son of God. Like many such syntheses, it is often not clear who was culturally appropriating whom. Certainly, throughout the Middle Ages, Christmas festivities like the 12 days of saturnalian debauchery, the veneration of the holly and mistletoe, and the Feast of Fools were all continuities from pagan Europe.

For this reason, the Puritans abolished Christmas. As late as the 1860s, Christmas was still a regular work and school day in Massachusetts. By then, however, its reconstruction was well on the way in the rest of the nation. America drew on the many variants of Christmas brought over by immigrants. It is telling that, in the making of Santa Claus, it is the English Father Christmas, derived from the pagan Lord of Misrule, rather than the more Christian Dutch St. Nicholas that dominates.

The commercialization of the holiday began as early as the 1820s, and by the last quarter of the 19th century a thoroughly unique American complex had emerged--ornaments, Christmas trees and the wrapping of gift boxes. Christmas further evolved in the 20th century with department store displays, Santas and parades, the outdoor Christmas tree spectacle, postage cards and secular Christmas songs. All American ethnic groups contributed to this national ritual.

The re-Christianization of the holiday emerged in tandem with its commercialization during the 19th century. Secularists did not distort or steal Christmas from Christians: in America they made it together. What's more, as the cultural historian Karal Marling shows, the festival's most compassionate aspect, charity, came mainly from the influence of Dickens's "A Christmas Carol," which, however, drew heavily on the largely invented accounts of a romanticized Merrie Olde England by the American travel writer Washington Irving.

The outcome of all this is a uniquely American national festival perfectly attuned to the demotic pulse of the common culture: its openness and vitality, its transcending appropriation of eclectic sources, its seductive materialism. It is, further, a mainstream process that dovetails exquisitely with more local expressions of America like Hanukkah and Kwanzaa, the former a reinvention of a minor Jewish rite, the latter a pure invention, in a manner similar to the wholly fictitious Scottish highland tradition that pipes up around the New Year. Kwanzaa borrowed heavily from Hanukkah, right down to the menorah, in fashioning the American art of mirroring the mainstream while doing one's own ethnic thing. Decorating public Christmas trees with menorahs should be a soothing natural development in this glorious hall of cultural mirrors.

Ejecting Christmas from the public domain makes little sense, and not simply because religion only partly contributed to its emergence as a national rite. It should be possible to enjoy Christmas while recognizing its muted Christian element, even though one is neither religious nor Christian, in much the same way one might enjoy the glories of a Botticelli or Fra Angelico in spite of the unrelenting Christian presence in their art. In much the same way, indeed, that one might enjoy jazz, another gift of the mainstream, without much caring for black culture; or the American English language that unites us, in spite of Anglo-Saxon roots that are as deep as those of Father Christmas.

THAT FINAL THOUGHT I PROMISED (THREATENED?)

I don't really have strong feelings about Christmas one way or another. I can even be inspired by the myth of the baby Jesus as celebrated, for example:

I don't really have strong feelings about Christmas one way or another. I can even be inspired by the myth of the baby Jesus as celebrated, for example:* in Handel's Messiah. Isn't it enough of a miracle that "For unto us a child is born"? Especially if he happens to be "the prince of peace"? Of whom the ineffably beautiful alto aria sings, "He was despis-èd, and rejected of men. A man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief."

* in Berlioz' L'Enfance du Christ. In the great opening narration, which I've still never heard performed really well, the tenor sings: "Now learn, Christians, what a monstrous crime was then suggested to the king of the Jews by fear--and the heavenly warning that, in their humble stable, was sent to the parents of Jesus by the Lord." It's just an innocent infant we see being saved by his parents' unhesitating departure, leaving behind a heartbreakingly caring chorus of their shepherd friends, fleeing to Egypt, where we see the holy family, on the brink of death from starvation and thirst, saved by the unhesitating and unstinting generosity of an Ishmaelite family. There is a moment of ineffable tenderness when Joseph, restored to health, introduces his family to his hosts, and the Ishamaelite father, learning the baby's name, sings, "Jesus! What a charming name!" And then a moment of surpassing humanity when the men discover that they are both carpenters.

So, you see, there is material in the Christmas story that can stand as inspiration for us all. It just doesn't often come to the fore. (I think one reason I can't recommend a really satisfactory recording of Berlioz' L'Enfance--see below--is that so many performances are smothered with a fake piety that isn't in the score at all.) It's also, I think, not at all what Professor Patterson is talking about.

And as to his notion that this is a holiday for us all, I wonder if he ever had the experience of being a Jewish kid in a public school, surrounded by mostly Christians, being forced each year to sing "Silent Night." I guess it's been awhile since that sort of thing was allowed in public schools, and I rate that a good thing.

Christians, after all, have plenty of time to sing about round young virgins in their own place and time, don't they? It really isn't essential to their faith to bully anyone who doesn't toe their party line into submission, is it? Well, maybe it is. Maybe that, way more than the secularization of Christmas, is the mark of the debased spectacle "junk" Christianity has descended to in our place and time.

RECORDINGS OF MESSIAH AND L'ENFANCE

Recommendations are hard to make because: (1) There have been lots of good recordings of Messiah (but also lots of mediocre and outright bad ones), (2) there hasn't, to my knowledge, been a single really satisfactory recording of L'Enfance, and (3) in any case, I have only the sketchiest idea of what's actually available now--or even, often, what "available" even means in today's record market. So let me just make some suggestions:

* MESSIAH

It was when listening to an old 78-rpm recording conducted by Malcolm Sargent--on actual 78s, in fact--that I first heard the tenor singing the oratorio's first vocal number, the recitative "Comfort ye, my people," as singing to me personally, all the more so when he continued with the message from "your God": "Sing ye comfortably to Jerusalem, that her warfare is accomplish-èd, that her iniquity is pardon-èd." That tenor was James Johnston, hardly a household name, but the performance still moves me to tears in the so-so American Columbia LP dubbing I have.

Sargent (right), who wound up Sir Malcolm, wound up recording Messiah four times--two of them in stereo!--and I wouldn't give up any of them. Well, maybe the first LP version? He was an old-fashioned conductor, was Sir Malcolm, which in the case of Messiah means very little interest in "correct" baroque performance practice. But he was also as deeply musical a conductor as I know of. He is most often thought of as a fine choral conductor and conductor of English music, which he undoubteldy was, but he was also a fully worthy concerto partner for countless soloists, including--and this is saying quite a lot--the great Artur Schnabel in the Beethoven piano concertos; he made a gorgeous recording of Smetana's quintessentially Czech cycle of tone poems Ma Vlast; he made Gilbert and Sullivan recordings with a dimension that no other conductor has looked for. I'm sure I must at some time or other have heard a Sargent performance that seemed to me less than totally musical, but I don't remember it.

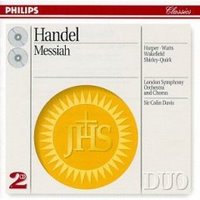

Sargent (right), who wound up Sir Malcolm, wound up recording Messiah four times--two of them in stereo!--and I wouldn't give up any of them. Well, maybe the first LP version? He was an old-fashioned conductor, was Sir Malcolm, which in the case of Messiah means very little interest in "correct" baroque performance practice. But he was also as deeply musical a conductor as I know of. He is most often thought of as a fine choral conductor and conductor of English music, which he undoubteldy was, but he was also a fully worthy concerto partner for countless soloists, including--and this is saying quite a lot--the great Artur Schnabel in the Beethoven piano concertos; he made a gorgeous recording of Smetana's quintessentially Czech cycle of tone poems Ma Vlast; he made Gilbert and Sullivan recordings with a dimension that no other conductor has looked for. I'm sure I must at some time or other have heard a Sargent performance that seemed to me less than totally musical, but I don't remember it. But we digress. The coming of "authenticity" to the baroque repertory started out encouragingly, and in fact produced one truly great Messiah: Colin Davis's first Philips recording, with the London Symphony and a fine group of soloists. Davis has always struck me as an almost incomprehensibly variable conductor, and many of his most famous performances seem to me of no interest whatsoever. But man, does that first Messiah hold up! (The fine contralto Helen Watts sings a memorable "He was despised.") Davis's later recording, with Bavarian Radio forces (for such an English piece? hey, don't ask me), doesn't have that same sense of every-number-in-the-moment rightness, but is still pretty good, and also has a pretty good solo roster.

But we digress. The coming of "authenticity" to the baroque repertory started out encouragingly, and in fact produced one truly great Messiah: Colin Davis's first Philips recording, with the London Symphony and a fine group of soloists. Davis has always struck me as an almost incomprehensibly variable conductor, and many of his most famous performances seem to me of no interest whatsoever. But man, does that first Messiah hold up! (The fine contralto Helen Watts sings a memorable "He was despised.") Davis's later recording, with Bavarian Radio forces (for such an English piece? hey, don't ask me), doesn't have that same sense of every-number-in-the-moment rightness, but is still pretty good, and also has a pretty good solo roster.More rigidly enforced "authenticity," where supposed correctness takes the place of musical insight and conviction, has gone far toward making Messiah and the rest of the vast baroque repertory a parched wasteland. And in the case of Messiah, there's an additional issue: the dimension of cosmic vastness that the wicked old Victorians imposed on the score. The only thing is that they were right. What they heard in this enormous score is clearly there--and it's not hard to understand why as deeply feeling a conductor as Sir Malcolm Sargent refused to give it up.

For this dimension of Messiah, if you should happen to see Sir Thomas Beecham's last recording of it, the RCA stereo one, revel in its sheer sumptuousness and joy. But the recording I would really suggest you watch for, which somehow manages to combine stylistic awareness with a willingness to pull out all the stops when the music cries out for it, is a wonderfully satisfying version that Andrew Davis (right--no relation to Colin, and actually the better conductor in my book) recorded for EMI when he was music director of the Toronto Symphony--with the American mezzo Florence Quivar doing a bang-up "He was despised" and bass Sam Ramey in top vocal estate ("The trumpet shall sound" indeed).

For this dimension of Messiah, if you should happen to see Sir Thomas Beecham's last recording of it, the RCA stereo one, revel in its sheer sumptuousness and joy. But the recording I would really suggest you watch for, which somehow manages to combine stylistic awareness with a willingness to pull out all the stops when the music cries out for it, is a wonderfully satisfying version that Andrew Davis (right--no relation to Colin, and actually the better conductor in my book) recorded for EMI when he was music director of the Toronto Symphony--with the American mezzo Florence Quivar doing a bang-up "He was despised" and bass Sam Ramey in top vocal estate ("The trumpet shall sound" indeed).* L'ENFANCE DU CHRIST

Boy, this is a tough piece to perform! Which I think is why it took me so long to "get." Berlioz is always hard. The tone is always so individual and precise--and changing, often from moment to moment--like that transition, in the opening narration, from Herod's monstrous crime to the miraculous heavenly warning.

One way you can guarantee getting almost none of it right is by slathering old-fashioned fake piety over the whole thing. A lot of the music lends itself to a kind of sing-songy soppishness that will simply destroy one of the most original and profound creations in the musical repertory. Another difficulty is that the vocal solo parts are extremely demanding but also not very long, which means that you don't often hear them sung by good enough singers--and even star singers who "walk into" a performance are seriously challenged by music that is so far from obvious.

As a result, even the recommendations I can make fall into the "better than nothing" category, and I'm especially worried here about the choices that are actually available.

As a result, even the recommendations I can make fall into the "better than nothing" category, and I'm especially worried here about the choices that are actually available.Still, overall, the best recording, it seems to me, is the '60s one made with French Radio forces (including some pretty good soloists) conducted by Jean Martinon (right), which the late Teresa Sterne found somehow and made a mainstay of the Nonesuch Records LP catalog. I don't know that it's ever made it to CD, but it's worth watching for.

Otherwise . . . hmm. Charles Munch was a great Berlioz conductor, and he made a number of important Berlioz recordings for RCA while he was music director of the Boston Symphony. The L'Enfance, though, is dangerously overromanticized, and the brand-name soloists aren't as good as you would hope. Still, these are quality musicians, who have at last a general idea of where the piece is going.

And then, well, there was a pretty good 1959 Paris recording conducted by Pierre Dervaux for Ades, with maybe the best Narrator I've heard, the character tenor Michel Senechal (right), and a memorable Herod from the fine bass Andre Vessieres. (I'm not so happy about the Marie and Joseph.) And I do get some message from the audio portion of a 1985 Thames Television performance, issue by ASV, with the English Chamber Orchestra conducted by Philip Ledger. (Has the actual TV version been issued on DVD?)

And then, well, there was a pretty good 1959 Paris recording conducted by Pierre Dervaux for Ades, with maybe the best Narrator I've heard, the character tenor Michel Senechal (right), and a memorable Herod from the fine bass Andre Vessieres. (I'm not so happy about the Marie and Joseph.) And I do get some message from the audio portion of a 1985 Thames Television performance, issue by ASV, with the English Chamber Orchestra conducted by Philip Ledger. (Has the actual TV version been issued on DVD?)ANYWAYS . . .

Happy holidays to all!

1 Comments:

Gifting ought to be a way of life for us all year long. I think that is why I enjoy the holiday. It should be that we gather more than annually to express love and enjoy each other's company. When Americans finally wise up and get the same work schedule as Europe and the Scandinavian countries, we might find time for such activities throughout the year. Then, we would not stress so much at the once.

Well, there are a lot of thoughts in there, think about it.

Post a Comment

<< Home